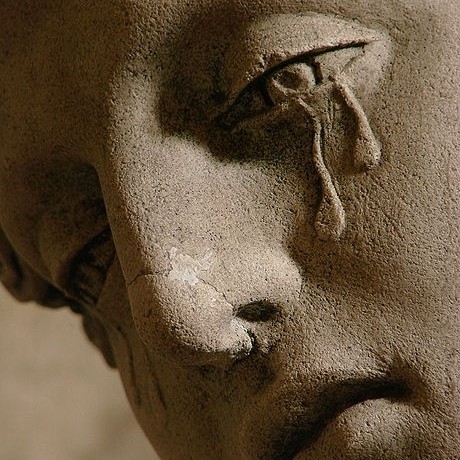

Image Source: Prof. Dr. Franz Vesely, Viktor-Frankl-Archiv, Wikimedia Commons

When acceptance of assisted suicide was written into Canadian law earlier this year, one of the criteria for it became this: that the person “have a grievous and irremediable medical condition” which is defined, in part, as an “illness, disease or disability or …state of decline [that] causes them enduring physical or psychological suffering that is intolerable to them and that cannot be relieved under conditions that they consider acceptable.”

Everyone suffers at some point or another, but most do not select suicide. So to suffer so much that one chooses death over life is to suffer to the point of despair. Rather than assisting with a despairing person’s suicide, we ought to instead consider the insight of psychiatrist and Holocaust-survivor Dr. Viktor Frankl. In this interview he talks about the following mathematical equation his observations and lived experiences caused him to create:

D = S – M

He explains it as follows: Despair equals Suffering without Meaning. Some people get cancer. Others get hurt in car accidents. These are very real cases of suffering—not to be minimized. But whether someone despairs in light of these experiences is in direct proportion to whether they find meaning in the situation or not.

Dr. Frankl cites a teenager in Texas who became a quadriplegic—undoubtedly, an experience of suffering. And yet she did not despair as others in her situation have. What set this young woman apart was not her experience of suffering but her response to it: She spent her days reading newspapers and watching the news for an important purpose—whenever there was a story about someone experiencing difficult and challenging times, she would ask that a stick be placed in her mouth so she could use it to press keys to type out letters of encouragement, consolation, and hope to the people she read about. Dr. Frankl said, “She’s full of confidence. She has a strong sense of abundant meaning in her life.” She turned her experience of suffering into a springboard to reach out to others; it enabled her to have empathy and share hope. In short, she found meaning.

Or take another person with quadriplegia, a young man who became paralyzed at 17 years old. Dr. Frankl received a letter from him: “I broke my neck but it did not break me. I am at present helpless and this handicap will remain with myself apparently forever.” Why, like the aforementioned young woman, did this man not despair? Because he found meaning in his situation: “I want to become a psychologist to help others,” he said in explaining his decision to pursue post-secondary education. “And I’m sure that my suffering will add an essential contribution to my ability to understand others and to help other people.”

When speaking of individuals like the two mentioned, Dr. Frankl noted, “They can mold their predicament into an accomplishment on the human level; they can turn their tragedies into a personal triumph. But they must know for what—what should I do with it?”

The brilliance of this philosophy is that it empowers everyone. While we cannot necessarily escape suffering, we can escape despair, and we can escape it in direct proportion to the meaning we allow ourselves to find in a situation. In other words, when circumstances prevent us from eliminating suffering, perspective allows us to add meaning, and that, in turn, helps alleviate the suffering itself.

This can happen in profound ways. Dr. Frankl told a story about a man who was electrocuted and all four of his limbs had to be amputated. That patient wrote, “Before this terrible accident I was bored, always bored, and always drunk. And since my accident I know what it means to be happy.”

This is proof that happiness is not determined by physical wellbeing but by an attitude of the mind. So if someone is struggling in this area and requests assisted suicide, it’s our job—not to facilitate their despair—but to facilitate their search for meaning.

If a Holocaust survivor, amputee, and quadriplegics can do this, why can’t we all?