“I just wanted to thank you,” I started to say, as the tears began too. I didn’t want to cry when conveying my gratitude. Maybe it was the pregnancy hormones. Or maybe it was the gravity of what she had done in sharing with me. But there I was, blubbering away as I tried to get the words out.

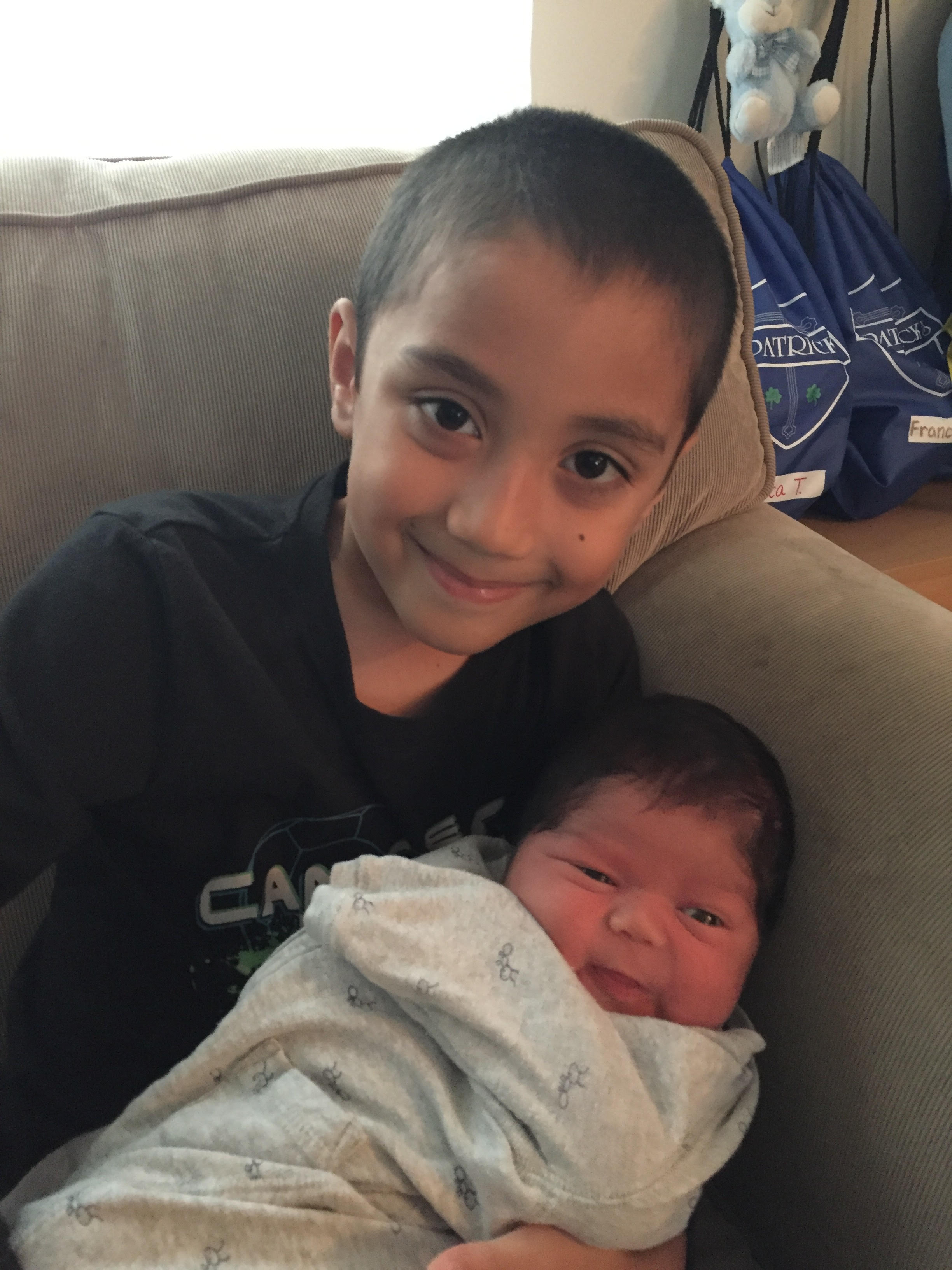

I was at a minor medical appointment related to my ear with my Nurse Practitioner. I hadn’t seen her in a while. Coincidentally, the last time I was in her office was one year prior, almost to the day. On that previous occasion, I had been on the tail end of a third miscarriage. Fast forward to the present appointment, and I was pregnant again. This time, everything is going well with sweet one growing in my womb. And as my burgeoning, 22-week belly beckoned her attention, so did my tears and words.

When I had seen my NP twelve months ago for another minor issue (my pregnancies were being handled by OB care), I happened to share my many miscarriages with her. And she shared with me that she had had two miscarriages. And no more children—by choice. By choice, she conveyed sadly, at the time. She then said, “I regret not trying again. I regret not trying for more children.” Fear had kept her back. Now, with the reality of aging, it was too late. But she was sharing what she regretted with someone—me—who was younger and could learn from her.

“I just wanted to thank you,” I said at my appointment the other day, “For sharing with me back then that you wished you’d tried for more.” I conveyed to her how grateful I was to have tried again, to be pregnant with this baby.

But in between her words a year ago and this second-trimester pregnancy I am currently experiencing, was to be for me yet another—a fourth—miscarriage. When my husband and I found out last spring, at a routine 12-week pregnancy appointment, that our fifth child had died like his three older siblings, my shattered spirit cried out in anguish, “I never want to get pregnant again.”

My reaction to so much death of not wanting to be pregnant again, was a natural, human response to suffering. It was the reaction my nurse practitioner had once had too.

But both of us could ultimately recognize that such a response was based on fear. It was based on the fear that a subsequent pregnancy would result in yet another miscarriage. And it could. Three in a row surely taught me that. But it also could lead to a live birth. A myriad of medical tests turned up no explanation for my losses. I have been under incredible care from a top notch physician in the world of restorative reproductive medicine/NAPRO Technology. Other than a need for progesterone supplementation (which I’ve had for five of my six pregnancies), no pathology has been identified. There is nothing to fix.

If I avoided pregnancy again I would have the guarantee of avoiding another miscarriage. But then I considered the future. And wondered what it would be like to be 80 years old and look back and always wonder, “What if? What if we had given life another chance? What if the next child, or even children, would survive?” I didn’t want to live with that depth of regret looming over my future. If God bestowed more life on us, He would be in charge of its trajectory. But I didn’t want to be closed off to letting His life even enter my womb to begin with.

After one of our losses my husband wisely remarked, “If we’re going to be open to life, we’ve got to be open to death.”

It was a hard truth. When pregnancies proceed healthily and parents live to see their children’s children, when our society has access to top notch medical care and has low infant mortality, we can forget the reality that every living person faces an ultimate earthly destination of death. Since four of my children have died within my body, I have become keenly aware of that fact. I have experienced the fragility of life. And it has crushed my heart each time.

But it has also reminded me that this earth is not our home. It has reminded me that my children are very much alive in the Heaven that awaits me. It has reminded me that until our epic family reunion, my days are meant to be spent loving God and loving others better and better. It has taught me to live with an eternal perspective, to realize that the value of a child’s life is in that life—not in its length. It has taught me that the worth of my children is in who they are as unrepeatable, irreplaceable individuals made in God’s image; it is not based on how much time I get to spend with them on earth. My, and my children’s, ultimate destination is Heaven. How long we live on earth before getting there is not in my control. But loving life here until it reaches its destiny, however long or short that may be, is within my control.

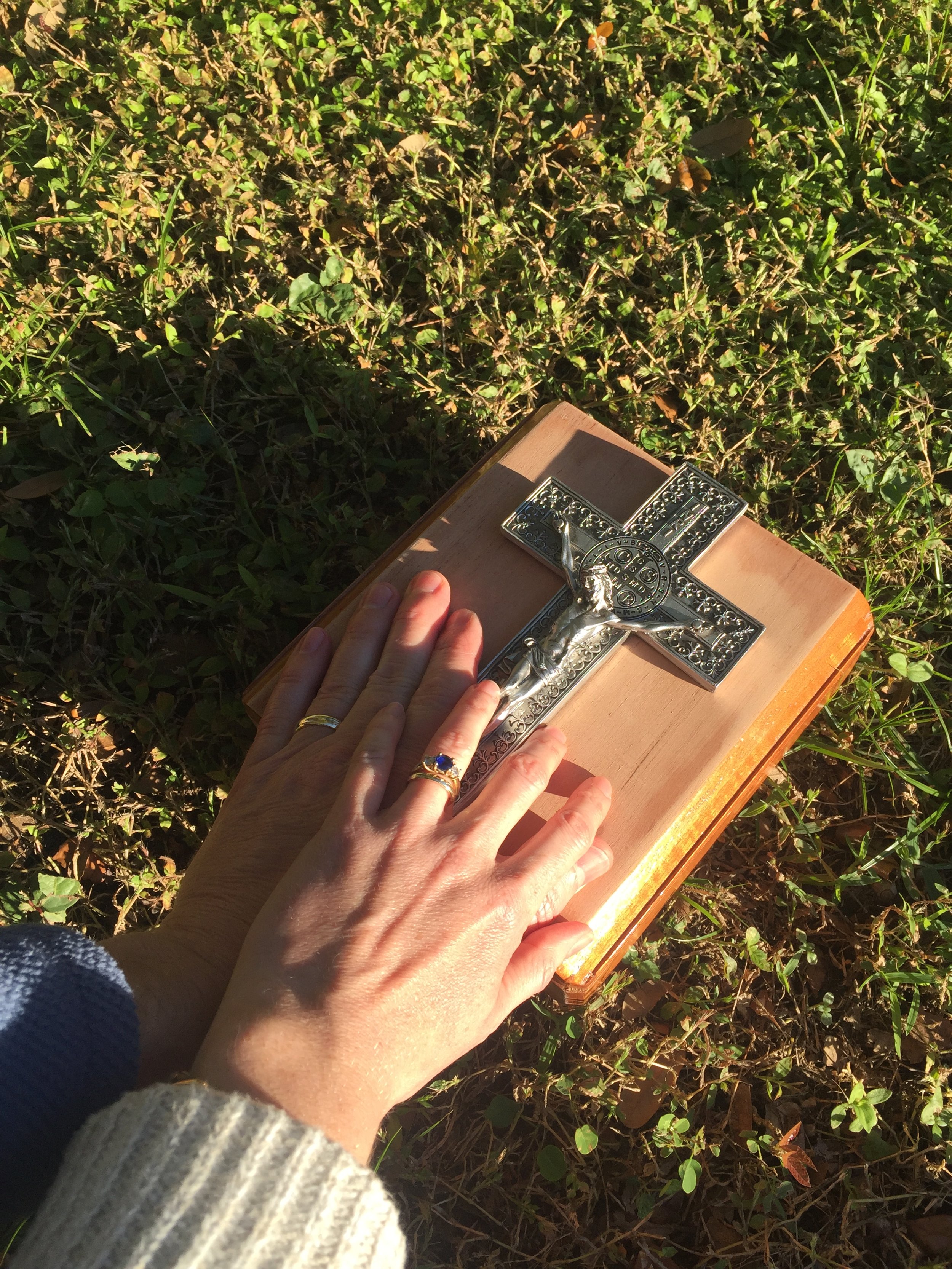

So here I am, pregnant again, a tabernacle again for the sacred, for a human body and soul described by his or her creator as “very good” (Genesis 1:31). The other day my 2-year-old was repeatedly saying what sounded like, “Body! Body” so I responded, “You have a body.” And then I said, “You are a body and a soul!” And she immediately said, “My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord” recalling the words of Jesus’ mother that my husband and I sing to her before bed. Yes, her sweet little toddler soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord, as does each of the souls of my other children, four of whom are doing so perfectly already at the wedding feast of the lamb and one of whom is kicking in my womb as I type this. My pregnant body also proclaims the greatness of the Lord; it proclaims that death is not the end of the story, that God is a God of life, and that the resurrection follows the crucifixion (incidentally, the last baby I miscarried I lost on Good Friday. The one growing in my womb today is due on Easter Sunday).

After my fourth miscarriage, a friend e-mailed me who had lost a pre-born child of her own. She wrote, “It may seem far, far from your present reality, but the joy your dear children are experiencing in their heavenly home right now is so very real, and wouldn’t be possible without you. Through God’s Mercy and your desire for their baptism, they are now saints. Thank you for your courageous love that allowed this.”

Courage, I once read, is not an absence of fear, but a will to do what’s right in spite of your fears. I don’t know precisely what the future holds, and at various times in this latest pregnancy I have been afraid. But regardless of my past sufferings and present unknowns, this new child is wanted and willed. I have come to see that when we choose life, we flourish. And when the thief of death rears its head in our broken world, I know that that isn’t the end of the story. I know that the depths of loss we experience when losing a beloved is a reflection of the heights of our love. I know that one day that love will be lived in perfect form in eternity, where, mysteriously, death on earth leads us to eternal life in Christ. Until then, I choose to be a worker building up His kingdom here on earth.