God

Although Peter Singer and I argued our positions from non-sectarian perspectives, I couldn’t help but feel, after the debate was done, that something—Someone—was missing.

Peter is known for being an atheist, and in a conversation with Andy Bannister he points to the existence of suffering in the world as being proof of the non-existence of God. Otherwise, he asks, how could an all-powerful, all-loving God not intervene to stop the suffering in the world?

A whole other debate would need to be had on this topic, and I point readers to the insights of philosopher Peter Kreeft as a great place for in-depth reflections on the question of God’s existence. I would, however, like to share these few thoughts:

First, if the presence of evil in the world is a sign God doesn’t exist, how do we explain the presence of good in the world? Couldn’t we say that the presence of good is a sign of God, and the presence of evil is a sign of an arch enemy of God, namely Satan? As we see in The Lord of the Rings or The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe, these forces of good and evil fight against each other and do battle, but the good eventually wins.

Second, God has intervened to stop the suffering in the world—He sent His son Jesus to take on the punishment of our sins for us. A world of eternal life awaits we who choose it and that world is free of suffering and will have no more tears. Why hasn’t that world come yet? Why hasn’t the suffering on earth ended already? I don’t have an answer for that but I do have an explanation for my ignorance: I am a mere human and I don’t know it all. Just as a child simply cannot comprehend everything her parent does, I do not have the capability, with my limited nature, to comprehend everything God does. I am not all-knowing and not all-seeing, but God is. And because He is all-good, then I trust Him when I don’t understand (just as children ought to do with their loving parents). As mentioned above, Peter would cite the ongoing presence of evil as a sign God cannot be all good. But not everyone with that observation comes to that conclusion.

Take, for example, an article Peter wrote in 2011 about the death penalty. In particular, he commented on the possibility that some people who are given the death penalty may be innocent. He cited the story of Michael Morton who was unjustly incarcerated for 25 years for a murder he didn’t commit. I don’t know how much Peter has looked into Michael’s story beyond the bare facts, but I have studied Michael’s experience extensively, speaking and writing about it on various occasions. Michael suffered brutally, not only losing his wife to murder, not only being put in prison for a crime someone else committed, not only being deprived of raising his only son, but he endured more than two decades of lost freedom and horrific conditions in jail. If anyone could use the presence of suffering as grounds to say God doesn’t exist, it could be Michael. And yet, Michael doesn’t. In fact, he does just the opposite. In his memoir he writes, “I know three, little, simple things. One, God exists. Two, He is wise. And three, He loves me.”

When I think of Michael’s story as it relates to God, I imagine the following: What if it didn’t take 25 years to find the actual murderer of Michael’s wife? What if the guilty man was found within days? What if there had been clear evidence of his guilt and he was charged with murder? What if, when the guilty man was being sentenced to prison for life, Michael were to have stood up in the courtroom? What if Michael had said to the judge, “Your honor, I know this man is guilty of killing my wife. I know the just punishment for his crime is life in prison. But I would like to take his place. I would like to take on his punishment for him. Send me to jail instead.” We cannot even imagine Michael saying that. And yet, that’s what Jesus did for us. All of us are imperfect, and all of us have violated God’s laws. There are consequences for doing the wrong thing (read Chapter 1 of The Bible’s Book of Genesis). And if each of us were on trial in a courtroom for our various misdeeds, we’d be found guilty as charged. Imagine a just judge dealing out the punishment to us that aligned with our crimes. Then imagine Jesus entering the courtroom. Imagine Him saying, “Excuse me, your honor. I know that’s the consequence she deserves for the crimes she’s committed. But I’m here to take the consequence on for her so she doesn’t have to. Whatever her sins deserve, do it to me instead.” What innocent person knowingly takes on the consequences of the guilty? A Jewish rabbi named Jesus. If you’ve ever wonder if God is all-loving, think of that.

Third, although it takes faith to believe in God, it also takes faith to not believe in God. For example, imagine you discover an exquisite piece of artwork and say, “Wow, who made this?” and I replied, “No one. It just appeared.” You would think I was mad. You would say, “Such design cannot just appear from nothing. It couldn’t have fallen from the sky. It must have a designer!” To believe that art exists without an artist takes great faith, and involves believing in the stuff of leprechauns and unicorns. I would suggest it takes less faith to believe in God. Granted, if all design requires a designer, then eventually we will trace everything back to creation’s beginning and say, “God made it” at which point someone could fairly ask, “Well who made God?” Because God is all powerful we can reasonably say, “Because He’s God He’s always been and always will be. I can’t fully understand it because I’m not God.” An atheist has to rely on faith and explain how the complexities of the human body, other species, nature, etc., came to be literally from nothing while not providing the explanation of a higher power orchestrating it.

Fourth, when labelling things as “good” or “evil” we are implying a known standard we measure things by. If there is no God, who, or what, determines what is evil and what is good? Without God, we are left to humans deciding, and humanity’s long standing history of human rights violations makes us less than good authorities on this matter.

Peter doesn’t seem to like the idea that all humans are special because it implies a belief in God who says we are special. So what’s the alternative? One could not believe in God but still think humans ought to be treated kindly by their fellow humans. This would be the assumption I mentioned in part 1 which we come to through intuition or because it is self-evident. It is the most inclusive position for even atheists to hold, because no humans get left out by this standard. Just as someone could be atheist and against racism, one could be atheist and against killing fellow humans (particularly believing it’s wrong for parents to kill their offspring). Having said that, human weakness often causes us to depart from the standard that we should treat members of the human family equally and kindly. All too often when a human gets in another human’s way, or has something we want, we come up with qualities, criteria, and features that includes ourselves and excludes those whose elimination we wish to justify. Whether it’s ethnicity, religion, sex, sexual orientation, disability, cognitive level, or age—determining whether a human is protected based on qualities like these inevitably excludes some humans.

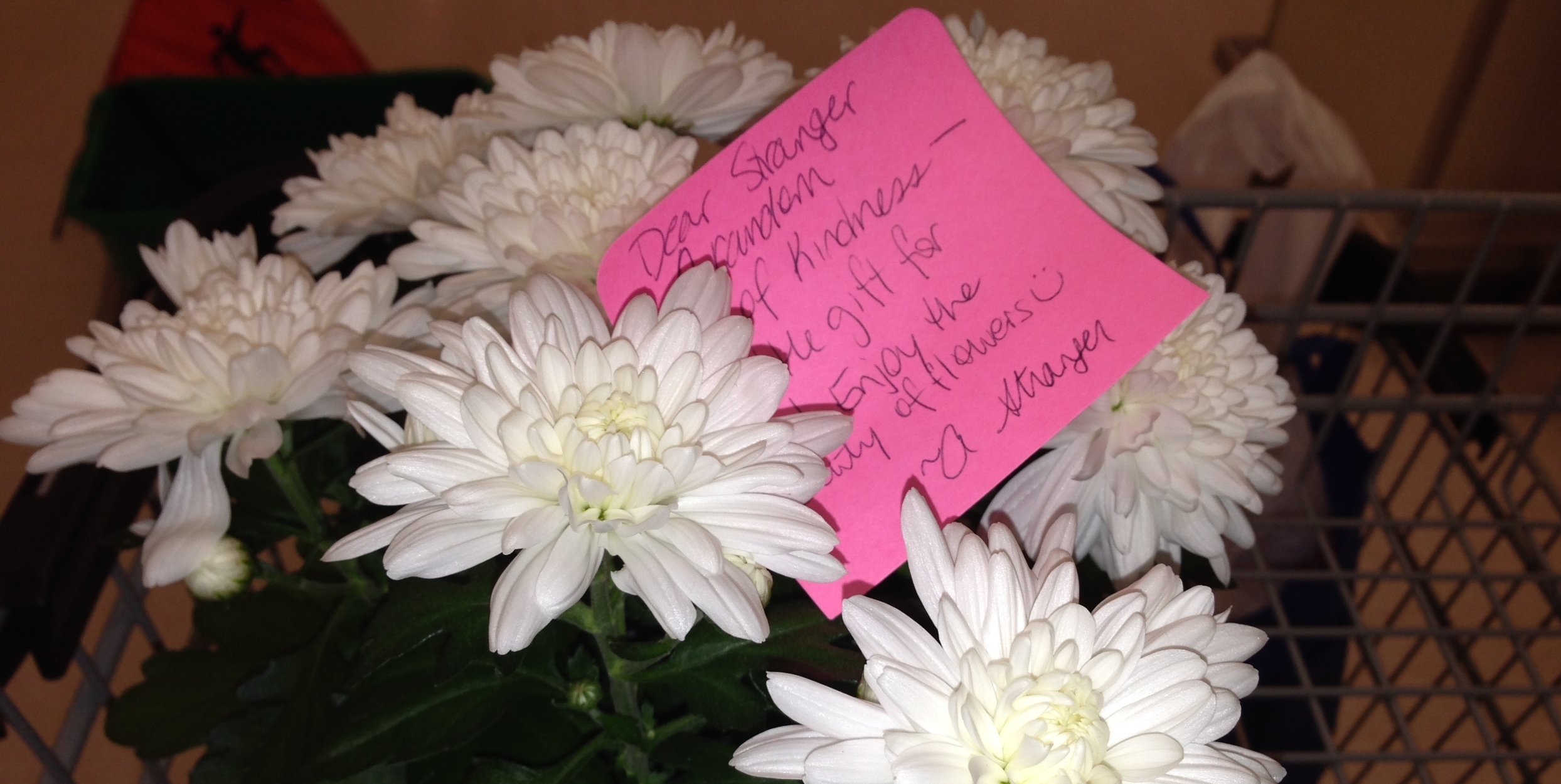

The fifth, and final, point is this: God could have made us like robots so we were forced to choose Him and never disobey His commands. But such choosing wouldn’t be authentic; it would be programmed. It would therefore be meaningless. No person wants to marry a beloved who is forced to say “I do.” Instead, we want to know the other party, in freedom, willingly chooses a lifetime together. The pursuer may romance his love interest, and entice her with all kinds of things like flowers, love notes, and gifts, but at the end of the day, she still must decide in freedom if she wishes to give her assent. Likewise, God romanced humanity by blessing us with relationship and beauty of all kinds, but He still gave us the opportunity to choose Him—which meant we also could reject Him. God had forewarned Adam and Eve of the consequences of violating His command and, as a person of integrity, was a man of His word and followed through when they rejected Him. But at the same time, as a Father and lover, He got creative about both following what He said and giving His creatures a path of redemption—salvation. As with Adam and Eve, we each have an unfolding story and we, like them, are given a choice—To choose God or reject Him. And as the history of the world shows, rejecting him leads to all kinds of devastation and suffering—the very things Peter is concerned about.

To return to the start of this series, click here.

Photo by Mads Schmidt Rasmussen on Unsplash