On Our Human Capacity to Love

After the debate, an audience member e-mailed me saying, “I've been wrestling with the sentiments Peter shared around suffering and humans with compromised capacities. Some of what he said greatly troubled me. What occurred to me this evening is that I think killing humans who present profound suffering or need profound care is not only an assault on that person, but one on our very selves. What I think many, including Peter, miss is that without these people calling forth love and care from us, we ourselves are diminished and hurt. I suppose like all great evils, it's masquerading as a good, a kind of cruelty clothed in false mercy, which makes it all the more difficult to unmask.”

This viewer’s sentiment expresses my observation too. Regarding his last point about cruelty clothed in false mercy, as I prepared for my debate against Peter, one of the things I found most challenging was that Peter doesn’t come across as monstrous the way some of his views are, which then makes his views that are monstrous appear as not so bad.

Peter and I had a private Skype call in advance of the debate, just to get to know each other as people without discussing contentious topics, a practice I’ve developed for my various debates in the last several years. We discovered a number of things in common, including our love of travel and hiking. He is an avid surfer and I have no doubt that my husband and he would have a smashing good time riding waves together. When my parents watched the debate, my mom observed that Peter seemed like a friendly and calm type of person (his soothing Australian accent is certainly to his advantage), and someone she could have an enjoyable conversation with, if she were to overlook his views on abortion and euthanasia. Moreover, Peter promotes “effective altruism” where he encourages people to share their wealth with the world’s poor; in fact, Peter himself is known for doing that with significant percentages of his income.

I don’t deny he has good qualities, and this is where there is an important lesson for we who disagree with him: Peter is no different than any of us; every single one of us is a flawed human being. We all have good sides, and corresponding bad sides. We all have qualities, beliefs, and behaviors worthy of emulating, and those that are not. The challenge is to have the discernment to not overlook the bad when someone demonstrates a good.

For example, Peter is known for propagating the drowning child thought experiment. If you see a child drowning in a pond, but in order to save the child you’d have to wade into the water and ruin your expensive shoes, should you do so? The obvious answer is yes, and Peter’s perspective here that we should rescue the child at personal inconvenience is a good one. On that, Peter and I agree. But just because he’s right about that doesn’t mean he’s right about abortion. In fact, his support of abortion would be analogous to having a child and then seeing a pond and subsequently intentionally placing the child into the pond to drown. If it’s wrong to leave a child to drown because you don’t want to ruin your shoes in rescuing the child, all the more it should be wrong to intentionally create a situation where you drown a child!

Of course, Peter would point out that if the child is aware and would suffer, then that should stop us from drowning the child. He would then point out that since pre-born children do not suffer from abortion (at least early abortion), then it is permissible. As mentioned previously in this series, something can be wrong even when it doesn’t inflict suffering. But I would also add this:

Holocaust-survivor and psychiatrist Viktor Frankl once said, “The salvation of man is through love and in love.” He also said, “The more one forgets himself—by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love—the more human he is…”

How can one be “more” human? Aren’t you either of the species homo sapiens or not? I think what Frankl is getting at here is, in a sense, what Peter Singer is getting at—that there are qualities or features that go beyond the physical reality of us. Peter focuses a lot on whether a being is rational, aware, has desires, or suffers. But even a psychopath can demonstrate all of those qualities. I would say there is something more to us humans than just those qualities. What that “more” is, is our capacity to love. And the more we love, the more we live up to our nature, the more we reach the fullness of what it means to be human (hence we would associate the word “inhumane” with cruel, unloving acts).

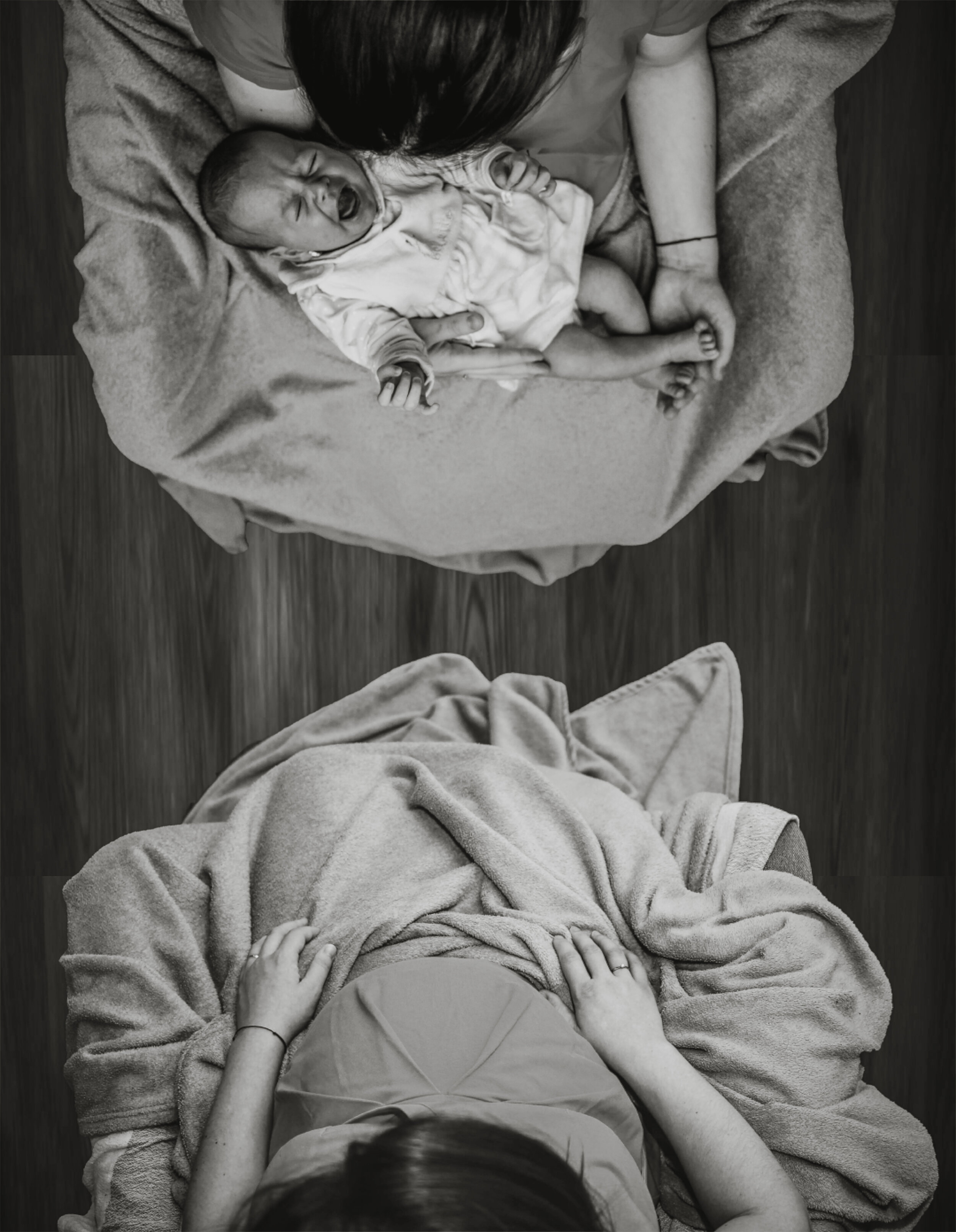

So what of those who are not developed enough to love? What of the child in the womb, or the newborn infant? Their inability to currently manifest love (or interests and consciousness to the level we know it) shouldn’t make them candidates for destruction. On the contrary, their immaturity in this regard should make we who are already mature be candidates for helping form them, for showing them what love is. And once someone comes to know love through receiving it, they can return love. Of course, even if someone doesn’t live long enough to develop the awareness needed to love back, it doesn’t absolve us of our responsibility to love them, to treat them with kindness, not cruelty.

Peter would perhaps consider this view utopian, but I fully recognize we live in an imperfect world and our call to love will not always be lived out properly. I am merely suggesting that while acknowledging that, it doesn’t justify intentionally inflicting (or promoting, or justifying) homicide on the youngest of our kind.

Photo by Steve Halama on Unsplash