A couple years ago I spoke at the March for Life youth conference in Ottawa where the topic was “Stump the Pro-Lifer.” Instead of giving my usual one hour presentation, the time was spent with me fielding questions from the audience—with attendees given the challenge of thinking of their toughest questions to confound me.

Most of the questions were typical of what I’d heard many times before, and in answering I was able to articulate basic pro-life apologetics, emphasizing that humans have human rights and because the pre-born are human, they have the same right to life as you and me. But then the question came, the question that (momentarily!) baffled me:

“If you believe in God,” an audience member asked, “and therefore claim that life is a gift from God, then how can you claim we have a right to our lives? After all, gifts are something given—they can’t be demanded; we can’t claim a right to have them.”

Suddenly 1,000 teenagers in the audience started hollering, cheering, and clapping. They felt it was a tough question and were excited to hear my response—was I stumped? Truth be told, I felt stumped; in trying to think of an answer, I took advantage of the audience’s reaction by trying to get them to extend their clapping: “Oooooooh,” I said, “Very good….grrrrrreat question,” I remarked as the audience laughed and cheered. My colleague, who was in the audience, later told me that she was trying to clap long and hard to drag out the time before I had to answer because she wasn’t sure if I had an answer either!

I silently called on the Holy Spirit for inspiration and began to speak. Truth be told, I wasn’t satisfied with what I started to say (nor can I remember it today), but then, about 30 seconds into my rambling, the inspiration came (Praise the Lord!). I explained my thoughts as follows:

Believing life is a gift and believing we have a right to life are not contradictory. To believe life is a gift means if I’m alive, then God loved me enough to will me into existence and my life is a gift from Him. Embracing human rights doctrines simply says once I’ve been given the gift, people around me may not take my gift away from me—my life is not their gift, it’s mine, so I have a right to ensure my gift is not unjustly taken from me; hence, I have a right to life. That’s why abortion is a human rights violation—it takes away the gift of life from pre-born children, a gift they have a right to have because they were given it, and a gift we don’t have a right to take.

The cheering began again. They were satisfied. Whew!

In reflecting on my answer in light of much news about euthanasia, it occurred to me that some might take this point but ask, “Even though someone doesn’t have a right to take my gift of life from me, if I don’t want it anymore, I can get rid of it, can’t I? After all, if I don’t want a gift someone gave me for my birthday several years ago, it’s okay for me to get rid of it, so isn’t it okay for me to choose euthanasia and get rid of my gift of life I no longer want?”

To answer that, we need to realize the following: The gift of life we’ve been given is so valuable it’s priceless. We’re not talking about getting an article of clothing that will go out of style. Instead, imagine being given a trillion dollars. It wouldn’t make sense to use only a portion of it and say, “I don’t want it anymore,” and then proceed to burn the rest. So too would it be wrong to live a portion of our lives and then prematurely destroy them. So if we don’t understand how valuable our lives are, then our job is to eliminate our incorrect understanding as to our worth, not eliminate our lives.

Moreover, think for a moment about the Giver of the gift of life: The Giver loves unconditionally and is perfect; He only wants our good. His judgment is better than ours. He takes great joy in giving us the gift of life. Can you imagine throwing a present in the face of a parent who lovingly gives his child a toy that will bring happiness? How, then, could we throw back at the face of an all-good God the gift of life He gave us?

To be sure, life on this earth has a natural expiry date that God built into it. We will die, and we all have to face our mortality. But if our Creator knows better than us about when that moment should be, then isn’t it our responsibility to steward the gift we’ve been given in the meantime? After all, imagine if that money was given with an expiry date—except you didn’t know when on the calendar that was. Wouldn’t you do your best with the resource you’d been given and not shorten the unknown time you have with it? Likewise, we do not know precisely when each of us will die, so we should embrace our invaluable resource until such time as it is designed to run out.

Now some might interject that if someone is suffering they can’t “do” much with their gift, so what’s the point? First, as I’ve written before, in such cases we should certainly alleviate suffering—just not eliminate the sufferer. Moreover, unfortunately in this imperfect world suffering is a part of life—it’s not something limited to those who are dying. And time and again, inspiring people, heroes, and role models, teach us to strive to overcome suffering and to turn obstacles into opportunities.

Holocaust-survivor Viktor Frankl, who saw some suffering people reject the gift of their lives by committing suicide in the concentration camps, wrote about how he decided he would not follow in their footsteps. He also tried to dissuade others from doing so.

He said, “We had to teach the despairing men that it did not really matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us…When a man finds that it is his destiny to suffer, he will have to accept his suffering as his task…His unique opportunity lies in the way in which he bears his burden...When the impossibility of replacing a person is realized, it allows the responsibility which a man has for his existence and its continuance to appear in all its magnitude…love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which man can aspire…a man who has nothing left in this world still may know bliss, be it only for a brief moment, in the contemplation of his beloved.”

Suffering is confusing. It is a mystery. But like many things in life, particularly those we don’t understand, what matters is what we do with them. St. John Paul II, in "Salvifici Doloris" (On the Christian Meaning of Human Suffering), wrote,

“We could say that suffering . . . is present in order to unleash love in the human person, that unselfish gift of one’s 'I' on behalf of other people, especially those who suffer. The world of human suffering unceasingly calls for, so to speak, another world: the world of human love; and in a certain sense man owes to suffering that unselfish love that stirs in his heart and actions.”

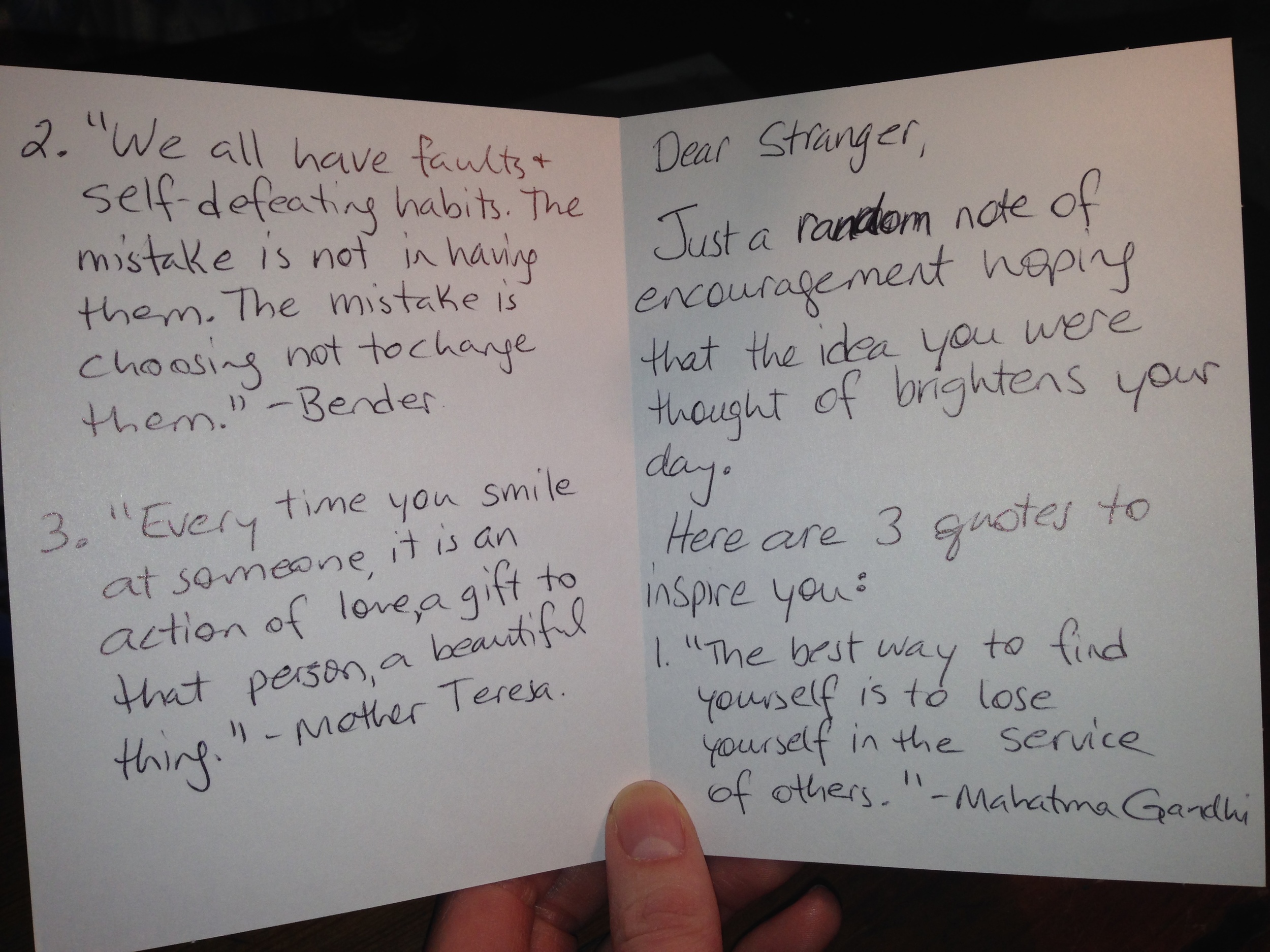

That point is well illustrated in an imaginary story (read here) about suffering people who don’t have elbows, and the different reactions one could have in their situation. Ultimately, their suffering led to love. And if there is no life, there can be no love. So we should respect the gift of life each of us has been given because it is with this gift, of an unknown duration, that we can love.