One year ago, shortly after 7am, on a morning I had planned to sleep in, I was awoken by a fire. Yelling startled me awake and when I looked out my bedroom window where I used to live in Brampton, Ontario, I saw that my breathtakingly beautiful place of worship, an all-wood onion-domed Ukrainian Catholic Church, was surrounded by fire trucks. Initially, I just saw smoke. But it quickly turned to flames. And it didn’t take long until the whole building was engulfed by a fiery inferno.

Six days before, I had experienced deep serenity as I stepped onto my patio to watch the setting sun light up the evening sky, illuminating the church’s dramatic silhouette. It was as though a piece of a Ukrainian village had fallen from the sky and landed in a field in Brampton, bringing quiet and peace to the most populated part of Canada, the Greater Toronto Area. People of all faiths and backgrounds regularly drove up to take in the awe and wonder of St. Elias the Prophet’s magnificent architecture. When people would walk in, they would be hushed by the presence of the sacred. The smell of incense and beeswax candles (the only form of lighting for the whole sanctuary, excepting sun beams shining through windows) were sweet to the senses. The floor to dome iconography that took 10 years to complete was breathtaking to behold. St. Elias was an experience of Heaven on earth. In every way, it drew the human experience to heights that went beyond this world.

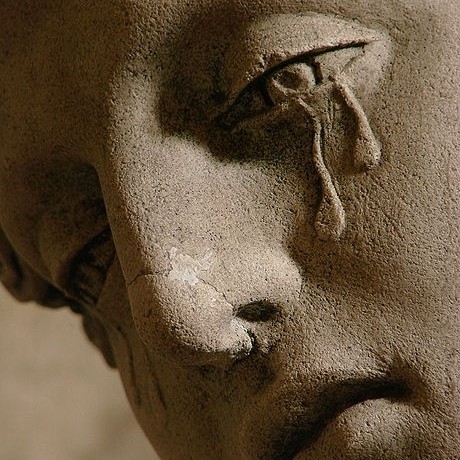

But less than one week later, I sat stunned and in shock as I watched St. Elias burn—literally—to the ground. I can’t quite get an image out of my head, of my dear shepherd, Fr. Roman Galadza, sitting on the frozen ground between the rectory and the church, his black cassock blowing in the bitter wind, head in hands, as he watched what he had labored to build for over 25 years disappear before his eyes. Agonizing.

I have so many memories from that day—hearing gut wrenching sobs, hundreds of people flocking to grieve, religious leaders of all kinds coming to express condolences, but what stands out most is two-fold, and both are Fr. Roman’s example. Amidst this loss, Father knew what was most important—who the church was built for, not the building itself. And so, with deep concern for the Body of Christ, he asked the firemen if they would attempt to rescue Our Lord. Donning their oxygen masks, several brave men entered the inferno and successfully collected the Body of Christ and His holy word—The Gospel Book. A fireman told me later that when he saw his colleague walking from the church, hunched over, carrying something wrapped in a blanket, he panicked thinking, “A body! Oh my gosh! There was a child in there.” No, there was not, but what—who—his colleague was carrying demanded a kind of reverence with which he so carefully cradled the Sacred, that which we would give to a precious child—and more.

Then there was what Father did only a couple hours after the fire. As more and more people flocked to the parish house, Father quickly prepared a prayer service for us all—and it was a service of thanksgiving. That is right: amidst anguish and loss, he immediately focused our perspective by leading us to give thanks.

In his booming voice he recited from Job 1:21, “The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away,” and we responded as Job once did: “Blessed be the name of the Lord.”

And a second time he boldly declared, “The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away!”

“Blessed be the name of the Lord!” we cried.

And a third time his voice thundered: “The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away!”

We shouted, “Blessed be the name of the Lord!”

This example has stayed with me ever since, and has been a source of consolation in trying times. It is easy to give praise when life is good—but can we give praise when life gets difficult? Can we maintain the perspective that no matter what we experience, God is good? Can we continually give God the praise He is due?

At St. Elias on April 5, 2014, it was so tempting to only lament what we had lost, but the leadership of Fr. Roman challenged us to give thanks for what we had received—to remember the 25 beautiful years the church building had been a sanctuary for prayer, praise, and healing.

Life delivers both joys and sorrows, and we cannot always control these. But what we can control is our response—and look for opportunities to express gratitude and praise amidst the most trying of times. Moreover, while objects may cease to exist, subjects do not. How much more tragic than the destruction of a beautiful building is the destruction of a beautiful soul? Protecting and nourishing the temple of the Holy Spirit should be our primary aim.

Indeed, each Sunday at St. Elias, and now in a school gym until the new church is built, the congregation lifts its voices and reverently sings,

“Let us who mystically represent the Cherubim, and sing the Thrice-holy Hymn to the life-giving Trinity, now lay aside all cares of life, that we may receive the King of all, escorted invisibly by ranks of angels. Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia.”

As we continue in this Easter season, let us remember that material possessions or not, we can receive the King of all. So let us lay aside all cares of life.