Last Friday as I flew to Texas to speak at a mother-daughter event, I stared out the airplane window at the majesty of the setting sun which had painted the sky red, yellow, orange, and blue in a breathtaking scene of beauty, and my mind wandered to a stark contrast: the turmoil going on back in my own country. February 6 was a dark day for Canada, for it was the day our Supreme Court overturned the law prohibiting assisted suicide.

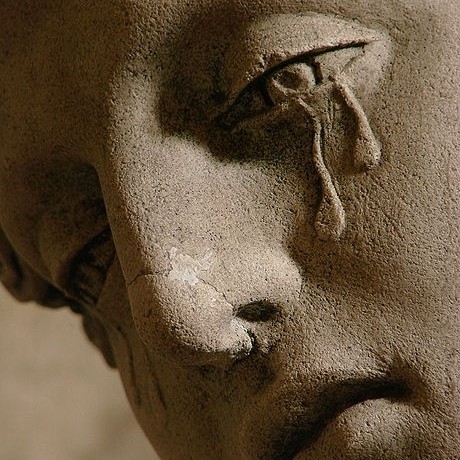

In between flights that day, I saw my newsfeed and e-mail fill with messages of deep sadness, fear, and dread. These were, and are, healthy reactions to a horrifying decision that attacks the dignity of the person.

Now that the news has settled over the weekend, it is good to take a moment to reflect on the importance of perspective. Holocaust-survivor Viktor Frankl, in his book Man’s Search for Meaning, reminds us of a truth we must cling to during these dark days: “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.”

The bad news is that the sick and vulnerable are in danger in Canada. The good news is that we are in control of our response to this horrible set of circumstances. No judge or government or individual can take away how we respond. So a question each one of us must ask is this: Are the sick and vulnerable, in my circle of influence, in danger? Each of us determines the answer to that question.

Consider Lord of the Rings, a story revolving around a young hobbit, Frodo, who inherits the Ring of Power and who is charged with the grave responsibility of transporting it to a volcano to destroy it. At one point, Frodo laments, “I wish the ring had never come to me. I wish none of this had happened.” And the wizard Gandalf, replies, “So do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.”

That is perspective. And that is what we must continue to come back to in light of the Supreme Court’s decision. While it is understandable that we lament, “I wish the court had never decided this. I wish euthanasia didn’t happen in Canada,” we should focus more on how we have the power to decide what to do with the time that is given to us, how we can choose our attitude in this present circumstance.

So what are we going to do with the time that is given to us?

I heartily recommend supporting worthy causes like The Euthanasia Prevention Coalition. Then, when it comes to a practical level, I think our primary response to Friday’s decision should be to love more deeply, and influence more positively, the people around us. If no one asks for assisted suicide, and if strong people protect weak people from medical personnel who would be tempted to kill the vulnerable, assisted suicide and euthanasia won’t happen. So what does that mean? Each of us, in our particular circle of influence, should seek out those around us who we can 1) be a friend to and 2) be an advocate for.

Be a Friend

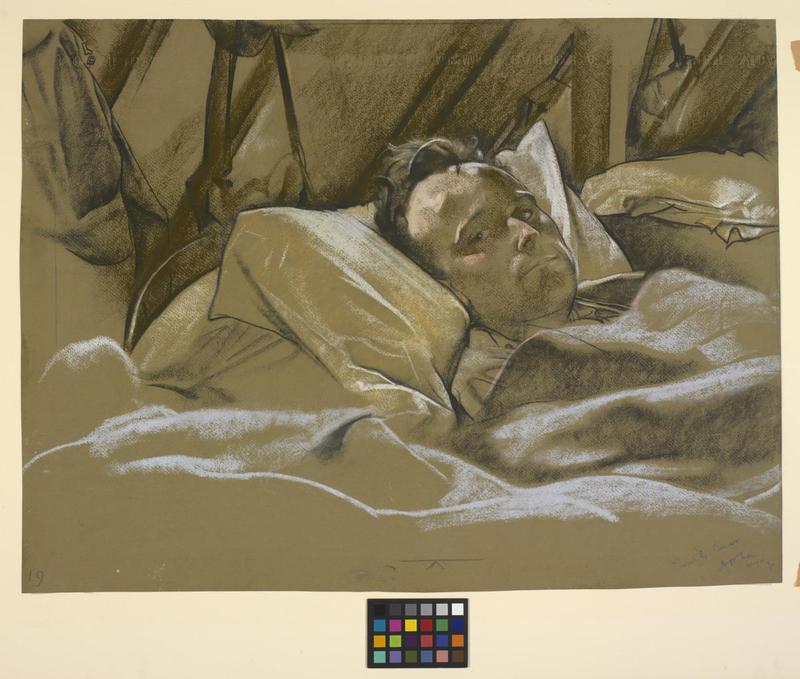

Many years ago, pro-life speaker Camille Pauley spoke about how she visited an elderly, unresponsive man in a hospital. She spent time visiting him not for herself, but for him. It didn’t matter that he couldn’t hold a conversation with her, because what mattered was that she communicated, by her time and presence and love, that he was valuable, that he was unrepeatable and irreplaceable, and that he had dignity by his very existence, not by anything he could do. By simply “Being With” (the name of the program she developed for this very outreach), she affirmed his worth. If someone is not made to feel like they are a burden, but instead made to feel that they are worthy of our time, they are unlikely to ask for assisted suicide.

Practically speaking, I think we all could do an inventory of our family and friends and think about one or two in our circle who most need special attention, and then be intentional about spending more time with them. We could also seek out one or two people we don’t yet know that we will make time for. I recently sent this message to my pastor and encourage others to copy and paste the same:

In light of the Supreme Court's decision to overturn Canada's prohibition on assisted suicide, I believe one of the best ways we can respond to this horrible ruling is for everyone to make sure that the people in their circles of influence don't ever ask for assisted suicide--to make sure that everyone in our circles of influence feels loved and supported and cared for.

So in asking, “What can I do?” it occurred to me that there could be someone at our church who is an elderly or disabled person who is shut in with no family or friends who could use some visits and help. So I was wondering if you know of a parishioner like this who could be blessed by someone forming a friendship to spend time with them? If so, could you please connect me to them?

Alternatively, signing up to visit at a local elderly home is another practical way to be present and loving to the vulnerable.

Be an Advocate

Besides being a friend, we also need to be an advocate. The dictionary defines this as “a person who speaks or writes in support or defense of a person.” If one of your family or friends is hospitalized, are you equipped to ask the right questions and seek out the right information to ensure their medical treatment is handled in an ethical fashion? Several years ago I took a certification course in health care ethics through the National Catholic Bioethics Center (NCBC) in Philadelphia. Thanks to the NCBC’s resources, when my friend with a brain tumor was facing possible end-of-life issues, I was able to share their advice for ethical decision-making with his wife.

Whether you know how to ethically handle end-of-life care (e.g., how does one determine whether an intervention is proportionate versus disproportionate?), or whether you know where to look for what is the right course of action, another important point for consideration is this: do you have the legal power to ensure the right thing is done for your loved ones? Last night I confirmed that I have Power of Attorney for my parents should they ever be incapable of making medical decisions on their behalf. This was a legal document I signed several years ago and you can bet, should it ever need to be enforced, that I will make decisions on their behalf that respect their dignity. You can bet I will ensure doctors respond by alleviating suffering, not eliminating the sufferer.

If you are a health care professional, you can advocate for your patients by practicing ethically and not allowing the Supreme Court’s decision to cause you to do anything different except that it motivate you to be more loving, attentive, and compassionate, someone who exemplifies what it means to be a part of a healing profession.

When we are tempted to be overwhelmed by the gravity and far-reaching consequences of the Supreme Court’s decision, let us remember that we are in control of our response. Rather than despairing or being overwhelmed, let us remember the words of Bishop Untener of Michigan who said, “We cannot do everything, and there is a sense of liberation in realizing that. This enables us to do something, and to do it very well.”

Be a friend. Be an advocate. Let us each do that very well.